EURO CRIME

Reviews

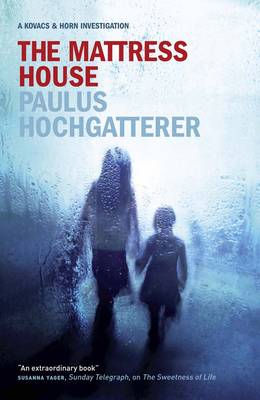

Hochgatterer, Paulus - 'The Mattress House' (translated by Jamie Bulloch)

Hardback: 256 pages (Jan. 2012) Publisher: MacLehose Press ISBN: 0857050281

Paulus Hochgatterer has followed THE SWEETNESS OF LIFE, which won the European Literature Prize in 2009, with another novel set in the same Austrian Alpine town of Furth am See. It's about human nature, rather than a 'crime novel' in the conventional sense. Nothing is described in a straightforward fashion, so the reader has to interpret events that are described indirectly, or that are filtered through the subjective view of a character, or that are simply fragments that may or may not be relevant to the whole. Although this approach can occasionally be a little frustrating, such as when one reads a segment about people but does not know who they are because they are not named, this short book about small-town secrets is, overall, very rewarding.

The two main characters (as in the previous book) are the police commissioner Kovacs and the psychiatrist Raffael Horn, though the book is certainly not "a Kovacs & Horn investigation" as the cover words state, as I don't think the two men even meet. Both are depicted as worrying and insecure about their roles as fathers and partners, in Horn's case this means his tense relationships with his wife Irene, a cellist, and younger son Tobias. Kovacs finds himself in love despite himself, as well as apprehensive about the impending visit of his 16-year-old daughter whom he has not seen since his divorce; the story of the daughter's visit is one of the most touching aspects of the book. As well as musing on their personal lives, both men's feelings about the groups of people they work with are a main theme. Kovacs runs the police department, speculating at length on its individual members; because of an absent colleague he has to pick up the case of a worker who fell from some scaffolding - was it an accident or not? Then, reports are received about children being attacked (but not seriously) by a "black owl". The parents are outraged and involve the media as well as Kovacs' superiors. None of the children will provide any details of their ordeal as they are sworn to secrecy.

Horn, a psychiatrist at the hospital, interacts both with his colleagues in various team and medical settings (he has an alarming tendency to speak his thoughts without realising it), and with a relatives' support group for people with family members in treatment. These settings are used by the author to explore psychological and neurological illness of various kinds. The police refer the children who were attacked to the unit, so Horn attempts gentle therapy sessions to try to see if he can learn more than the children tell the police, teachers or their parents. While this is going on, several of the other patients are depicted in detail, with past and present abuse of children coming more to the fore as the book continues. Both Horn and Kovacs separately worry about whether they have beaten their own children (they can't seem to remember!).

Other subjects are explored - the mad (?) priest with the iPod from the earlier book is around, here befriended by a woman who at first keeps him grounded but in fact may not be the stable person she seems. In a more disturbing plot, a story is told from the point of view of a young teenage girl who, with her much younger "sister", lives in a house from which she has escape routes marked out, and so on. It is not too much of a stretch of the imagination to work out in general what is going on here (particularly because of a prologue, surely an over-used device in modern fiction); but how the girls relate to the rest of the story is not revealed until the (rather abrupt) ending. At this time, other aspects shift into sudden focus, such as the scaffolding case - which again turns out to hinge on the alienation between parents and children - and of course the identity of the "black owl".

This is a hard book to sum up. In terms of language, it veers jarringly between present and past tense, sometimes between sections or chapters, sometimes within them. In terms of substance, the author likes to obscure clarity throughout, sometimes successfully, sometimes less so. For example one spends most of the book sharing Horn's frustration with Irene, his wife, seen entirely through his eyes - yet towards the end the reader's perception shifts and she is revealed in a sympathetic light. On the other hand, I was left somewhat clueless by the priest/woman story - is this my fault for not being clever enough to detect the author's subtlety, or was I supposed not to understand? I think the balance is wrong between the large amount of pages about Kovacs' and Horn's angst on the minutiae of their comfortable lives, and the small amount given to some of Horn's patients (especially the younger ones) who have or have had to deal with pretty extreme problems. Although written in an oblique, blurred and episodic way, there is much to gain from reading THE MATTRESS HOUSE, in its depiction of how people make assumptions about others, and of how societies and institutions hide the injustices done to those, mainly children, who have no outside source of help. I found the book sad and haunting, and highly recommend it if you don't mind a bit of work.Maxine Clarke, England

January 2012

Details of the author's other books with links to reviews can be found on the Books page.

More European crime fiction reviews can be found on the Reviews page.